Blog Archives

High school to college

An article about standardized schooling:

This quote struck me:

If you, as a higher education professional, are concerned about the quality of students arriving at your institution, you have a responsibility to step up and speak out. You need to inform those creating the policies about the damage they are doing to our young people, and how they are undermining those institutions in which you labor to make a difference in the minds and the lives of the young people you teach as well as in the fields in which you do your research.

Stuck in the Mode

A table for your consideration:

| Traditional Course | Online Course |

|---|---|

| Lectures | Lecture Videos |

| Written Homework | Online Homework |

| Discussion Section | Discussion Board |

| Talking with friends in dorm | Meet–ups |

| Talking to professor | E-mailing professor |

| Lab Sections | Simulations |

| Clicker Questions | Checkpoint Questions |

| Artistic Critique | Peer Evaluation |

| Recess | Stand up from the computer and go outside |

Now, as an exercise, place these things and list the equivalent:

- Peer instruction, done by the book

- Trust falls

- Meeting in an environment with customizable avatars.

- Seeing your student’s emotional state on his or her face

- Doing things you don’t want to do, without being a single click away from leaving

- Having wikipedia available when you answer every question

We can list dozens of things from in-person education that aren’t there yet in online education, and just as many that are potentially possible in an online arena that we can’t get in-person. Online education has exceptional potential. I think it has just as much as analogue education.

I think we’re strangling online education.

People sometimes ask me what I want to do with my career. I often tell them of the time a colleague was telling me about the differences between Harvard and MIT. While listening I had a vision that I was standing before an apple farmer, informing me as to the differences between a Braeburn and a Macintosh. See the stripes on the Braeburn, and the shading on the Mac? Taste the flavors of them, the grain of the fruit, the feel of their skin on your teeth. “These are such unique things!” says the farmer. “So different from one another.” And meanwhile, I dream of steak. I dream of shrimp bisque, of buttered raisin-bread toast, of black-pepper-carmel tofu, of red curry with butternut squash, of whole world of food. I dream of a thousand kinds of education, not just the orchard we have now, bright as the apples may be.

We make education small by restricting it to lectures in a classroom. We make our online courses weak by restricting ourselves to the classroom analogy.

What do I want to do with my career? I want to explore and help create the larger world of learning and education. There are thousands of people who grow apples, and their pies and applesauce and cobblers and Waldorf salads are quite delicious, but I crave wider things, and I think other people will be the better for tasting things other than just apples.

Panopticon

Here’s the tl;dr version: schools want to track their students so they know where they are all the time. And not because there’s been some sort of major rash of abductions; simply to fight truancy. And in some cases, to make money.

If you’ve been reading this blog, you probably have guessed that I think this is dumb.

You may say, “Hey, some parents are hard-working individuals who have to make it to work and just don’t have time to watch their kids walk in the door, or get on the bus, or what have you.” And that’s a valid response, because as a parent, that is a choice that you make. If you are too busy to ensure that your kids to to school, and to check up on them afterwards, you know, get involved in their life enough to see whether they’re doing their homework… that is your choice. You can choose to care more about your work than about your kids’ education. It is your call.

The same goes for school districts that allow their classes to become so overloaded that teachers can’t reasonably take attendance. When you’re on the school board or other funding agency, that’s your call.

Make the decision, but don’t pretend you’re not making it.

These new methods are attempts at a technical solution to a non-technical problem. Students who want to skip school will see it as a technical problem, and will apply a technical solution. It’ll be easy. Your uniform’s bugged? Hit the bathroom and change into the clothes you stashed in your backpack. Your ID card is bugged? Get a friend to carry it through the day. Set up a rotation – you skip on odd days, they skip on even days. Hell, give ten cards to one kid.

By trying a technical solution to a social problem, we make these things into nothing more than a game to beat (or cheat), a system to be beaten. It’ll be easy.

Technology is great; it solves a lot of problems. This is not one of them.

I haven’t even started in on the huge issues with tracking students in such an abusable fashion. Do we imagine that no one else will have devices to read these cards? That some stalker won’t set up a card-scanner to see which students walking past them at the mall go to which schools by reading the cards in their purses? It’s already been done with the chips in modern credit cards.

I don’t have an issue with tracking students. Schools do that already, mostly by eye. This new method could become creepy, but it’s not inherently so, depending on how it’s implemented. I do have an issue with schools who want to abdicate the responsibility of tracking their own students.

Look at what we’re doing here.

The parents don’t want the responsibility of making sure their kids go to school, so they say, “Let the schools handle it. We did our best, we raised them and got them out the door.”

Schools don’t want the responsibility of keeping track of students, so they put the burden on technology and the corporations that make it. “We shelled out for this new technology, we’re doing our best.”

Those corporations can now turn things on the students, saying, “They’re the ones who bypassed our system. They have to be held responsible; we did our best.”

And the students?

Just look at those wonderful role models they have. Every adult involved, each one, ditching the responsibility and claiming they did their best. What do you think the students will do?

This is not our best.

Morality in Heirarchy

If you are in any level of school administration, you need to read this article, passed on to me by a friend:

http://bradhicks.livejournal.com/459368.html

It boils down this lengthy report of the UC Davis pepper spray incident.

The key message is, over and over again, “failed to communicate.” To quote George Bernard Shaw, “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” The UC Davis administration and the police that they called in were both permeated with that illusion, for weeks, and the pepper spray assault was the result. Here’s an excerpt:

Chancellor Katehi, on her part, “thought she made it clear” that when police ordered the students to leave, they were (a) not to wear riot gear into the camp, (b) not to carry weapons of any kind into the camp, (c) were not to use force of any kind against the students, and (d) were not to make any arrests. But all that anybody else on that conference call heard her say out loud was “I don’t want another situation like they just had at Berkeley,” and Chief Spicuzza interpreted that as “no swinging of clubs.”

This sort of situation is constant throughout the report. When you have to say “I thought I made it clear,” you didn’t. When you have to say, “I thought I understood,” that’s a sign that you didn’t know what the hell was going on and you weren’t about to admit it.

Because you’d rather see other people harmed than have yourself look stupid.

If you have trouble looking stupid, if it really scares you to the point where you’d rather have someone else rub capsaicin in their eyes than admit your temporary, changeable shortcomings, then I’m sorry but the world needs you to not be in charge of anyone. If you need to gather your courage first, that’s understandable – but gather it quickly, and act. For me, it helps to consider it as setting an example to the students I work with: that anyone can admit their faults and work to correct them. That, to me, is a lesson worth embodying.

Separately, there is also the issue that several people had been given directives, or even orders, that were either impossible or illegal. From the chancellor to the police chief to the officers at the scene, these people attempted to complete those tasks.

If you are in a position of power, it can be very jarring when someone underneath you says, “What you’re asking us to do is wrong and I won’t be a part of it.” It should be more than just jarring. It should be a show-stopper, an instant halt to operations. People do not stand up and say such things easily or lightly. I’ve been on both ends in such situations, and I wish that I had listened more often, and listened better, when someone under me told me that what I was doing was wrong. I’ve also been the whistle-blower. Sometimes people listened. Other times they just took the whistle out of my mouth and patted me on the head like a dog.

Any one person involved in the chain could have stopped this. From the chancellor saying precisely what was or was not allowed, to the police chief refusing to allow riot gear and weapons, to the lieutenant, to the officers themselves. Someone should have stepped up and been the moral compass. Even one officer, even one, should have taken another officer by the shoulder and said, “Holy shit, stop spraying them.”

It would have been so simple.

This, to me, is one of the great failures of our educational system: that when human beings are given illegal or immoral orders, they do not immediately refuse. We do not truly think and speak for ourselves often enough; we want to have someone with us. We want to rebel en masse or conform and keep our heads down, as if by doing so we can avoid the moral consequences of our actions and the actions of our leaders.

We as human beings turn acts of moral fiber into acts of social or professional suicide.

There will always be people who make immoral decisions, sometimes intentionally, more often not. If we do not teach our students, and train our teachers, to stand against such decisions, we will be ruled by them.

What, Again?

I’ve mentioned that sometimes I intentionally post things after they would normally be considered “dead issues,” to bring them back into our awareness, because I think we shouldn’t forget.

I’m writing this on January 18th, the day of the Great Internet Blackout to fight the SOPA and PIPA bills. This puts me in the dangerous business of predicting the future, because I’m going to suggest that there will probably be legislation in the works right now on February 27th that does basically the same thing those bills tried to do. Hell, those bills themselves might still be around in some sort of cut-down format as people try to weasel them past.

Legislation is, sadly, not like a video game monster. We did not hit it with status effects and wear down its HP until it went “poom” and disappeared. (Besides, everyone knows status effects never work on boss monsters.) Someone will sneak it as an amendment onto the defense budget, or onto something else too big to vote down. It’s been done before. This time, unlike the indefinite detention of US citizens, we probably don’t have the option to take it to the courts. SOPA is probably not unconstitutional, just awful. If it ever passes, in any form, it is unlikely to get reversed.

Legislation is someone’s idea of the right thing to do – for the world as a whole, or for their company, or for them in particular. No matter how misguided or full of crap we might think that idea is, someone out there thinks that it is right. If it gets massive public backlash in its current form, it will show up in another form.

It’s like dealing with little kids – we told them they couldn’t have a cookie, but that doesn’t mean they can’t have a brownie, right? Maybe they can have a cookie while we’re not in the room? What about half a cookie? Can they have cookies for dinner? They need a cookie, to protect the Earth!

I’m putting this on an education blog because a) it’s so important that it’s worth talking about in any online format, b) the freeness of the internet directly impacts the quality of modern education both online and offline, and c) the idea that every teenager will perfectly understand and respect intellectual property laws is ridiculous. Do you really want a school’s website or a massive wiki site to get shut down just because a student posted something to which they don’t have the rights? That’s what SOPA and PIPA would have allowed – and perhaps still will.

We can’t count on a blackout like January 18th’s every time something like this comes up. Politicians know that. We need to make it clear in other ways as well.

Exponential Growth

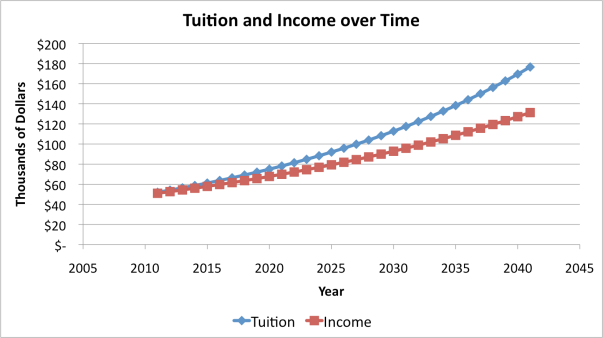

Middlebury College’s president got some press a while ago for capping the increase in tuition. Specifically, any tuition increases were capped at 1% over the Consumer Price Index, the standard measure of inflation in the US.

I’m not sure if whomever proposed this doesn’t understand exponential growth, or if Middlebury’s president didn’t understand it, or if he thinks that we don’t understand it, but I do, and let me explain it to you. Most of my data comes from Middlebury’s website, or comes directly or indirectly from the census bureau.

Middlebury’s total cost in 2010 was $50,400. This is a “comprehensive fee” that includes tuition, room, board, fees, and so forth. I’m going to assume that they won’t sneakily put massive increases into things other than tuition.

The median household income in the US in 2010 was $49,445.

The average rate of inflation in the US is 3.16%, averaging since 1958. Median household income grew at 0.04% over inflation since 1989. Naturally, these things fluctuate a lot as the market goes up and down, but those are the averages.

We can use this average to estimate the future tuition at Middlebury, and the future median income in the US. Here’s a graph.

If Middlebury’s tuition increases at their capped amount, the cost of going to school there will pass $100,000 per year in about 2027-28. This would be fine if we were all making $150,000 per year, but as you can see, we’re not.

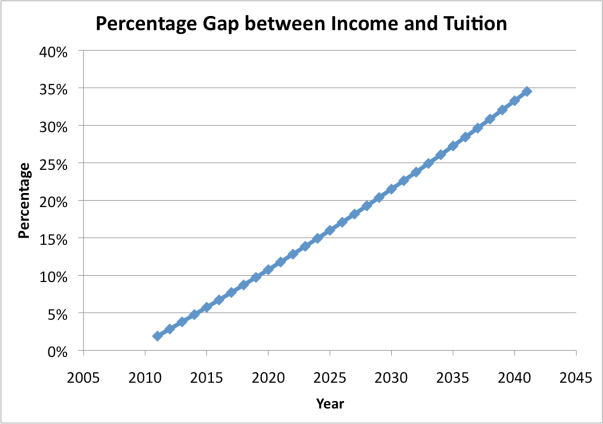

More instructive, perhaps, is the gap between median income and tuition:

You can see that by 2040, tuition at Middlebury will cost about 35% more than the median household in the US makes per year.

Sadly I don’t have good data for the amount of financial aid available and how that changes by year, but unless it grows at more than 1% over the inflation rate, it’s not going to help.

It is a truism in science that exponential growth can’t continue forever. Eventually the graph turns either cyclic or logistic, and the growth stops. Inflation is a special case; it can keep going forever because we can just revalue the currency to take some zeroes off the end of the bills, as Mexico did with the “new peso” in 1993. When something’s cost regularly increases at more than the rate of inflation, it will eventually need to stop because no one will be able to pay for it.

Exponential growth is a real killer. Middlebury’s plan is better than the average college’s increase. The average for four-year schools is about twice the inflation rate, which would lead to a massive disparity of 160% by 2040. However, it still doesn’t genuinely make the school more affordable.

The only way to make your school more affordable is to have your tuition increase at less than the rate of inflation. Anything more is still exponential growth.

Twenty Days and a Stack of Flash Cards

I know a secret teaching technique, which I can share with you.

With this technique, I can get any students to pass any standardized test in any subject. Not only will they pass, they will do exceptionally well. I guarantee a 95% or better. I can use this technique even in subjects that I don’t understand very well.

The technique is very simple. It requires only a few components. It does require a lot of time on the part of the students, but we won’t need a classroom or any special materials.

All I require is a few copies of the test, a copy of the answer key, twenty days, and a stack of flash cards.

At this point you have probably guessed the technique, but wait – I can do more.

I can also harm these students’ understanding of a complex subject. I can wreck not only their comprehension of fundamental concepts, but their long-term recall, their motivation, and their very understanding of what it means to “do” that subject. I can ruin their ability to do well in that subject so badly that others will spend years trying to undo the effects if the students don’t just give up first.

I can do this very thoroughly.

And I can do it in twenty days.

The same twenty days. Without changing my approach at all. It’s like a two-for-one sale.

Teachers make the Worst Students

Having run and assisted teacher training in a variety of situations, I can safely say: teachers make the worst students.

Oh, we may look innocuous and attentive, but we’ve learned from the worst. We pick up habits from every bad student we’ve ever had. The next thing you know we’re passing notes – “Do you like me? Circle one.” Or talking during class, or grumbling about what we’re asked to do, or working on something else when we should be learning. We decide that whatever’s going on isn’t worth our time, and that our side conversations are more important. Oh, let me check this text message, it’ll only take a second.

Don’t even get me started on role-playing exercises in a teacher training session. Talk about a minefield. Left to their own imagination, everyone brings in the worst attitudes from the snottiest kids from every class they’ve ever taught. Three jerks can ruin a class; imagine when everyone in the room is channeling twelve years of dissatisfied students. If you train teachers, and your intent is to run a class on classroom management, this is simultaneously your gold mine and your Hindenburgh – a gold-plated, explosive gasbag, if you will. Student attitudes begin to bleed over into teacher attitudes, and feelings get hurt as someone embarrassedly slinks back over the line of decorum. If your intent is anything but dealing with attitudes, you’ll need to set some explicit guidelines before you start.

Why are we like this?

After all, we’re adults – we get to be the “deciders” now. Why do we end up making such poor decisions? What makes us think that the things we’re doing are more important?

Who did we learn that from?

Who did they learn it from?

Education as Evolved Organism

Today’s post is a reflection on an article in Educause Quarterly: Is Higher Education Evolving? The core idea is that the educational system as a whole has some similarities to a culture – like a bacterial culture, not a social one – of evolved organisms, who adapt based on the evolutionary pressures on them. I recommend giving it a look, because it provides an alternative viewpoint, and I always find those useful.

An evolutionary pressure is essentially (and remember I’m not a biologist) something that forces a species to change. Often this “change” happens when half of the species dies off because the temperature changed, and the other half just happened to be prepared for the change. The action of evolutionary pressures depends on an inhomogeneity in the group that’s evolving – if everyone is exactly the same, then they’ll all die or live as a group. If some of them are different (as is the case with living beings), those whose differences allow them to withstand the pressures will survive to pass on those differences. Those that can’t survive might find a new niche elsewhere, if they’re lucky. More often they’re doomed. Evolution is a harsh mistress.

It is a sad statement about my level of optimism today that I can see only two real evolutionary pressures acting on education: politics and money. The quality of education delivered is not an evolutionary pressure.

The action of politics is clear in the proliferation of increase regulations and required standardized tests, among other things. Politicians come in with (in some cases) good intentions: to hold schools to a standard. Teachers who don’t want to teach to those tests either knuckle under or leave for greener pastures, and thus the schools evolve to fit the tests. Some of them evolve in unexpected ways, such as when teachers help their students cheat on the Regents Exam. (This is not speculative. A friend of mine worked in a school where this happened. She quit.)

Money as a pressure shows up in all sorts of unexpected places, but the clearest and most recent example is the explosion into online education. Where there’s money to be made, companies sprout up or move in to make it. Another example comes from the Aero/Astro department at MIT – as they began losing students, they changed the department to make it more appealing, and now the students (and their money) are back. Money may not be the motivation for the exact changes made, mind you. Teachers and professors and department heads genuinely want to educate their students. However, money is the pressure that forced the change.

As an educational researcher, I have to say that I don’t see quality of education as a believable evolutionary pressure. Unless it becomes a matter of public outcry (politics) or students become unemployable (money) or seek their schooling elsewhere (money), most schools and teachers (and universities and professors) are content to do what they’re doing now. The “revolution” in physics education research started about 25 years ago. The evidence that the standard lecture model simply doesn’t work is overwhelming. 25 years into the revolution, how are 99% of physics courses taught? By standard lecture. Even the opportunity for an overwhelming gain in the effectiveness of education hasn’t made a dent in what we do.

Let me say that again: we know how to teach better and, as a whole, we don’t. But this online thing? That’s where the money is. Let’s do it right now.

I’m a cynic today, but the lesson is this: if you want to change education, go into politics or business.

P.S.: Troy Roddy has a variant viewpoint over at The Art of Education, which is also worth a look. He’s talking more about “education” in the conceptual sense; how we view it. I’m talking about it more in the practical sense; the methods by which we achieve it.